Anthropology of Health

The following story appeared in the Summer 2019 edition of Baylor Magazine. Click here for the complete article.

In September 2015, Michael Muehlenbein, PhD, received an unexpected phone call from former classmate Katie Binetti, PhD, senior lecturer of anthropology at Baylor.

“I’d read some of his published work, and I knew that he had established himself at the forefront of biological anthropology, which is sort of a confluence of human health and anthropology and a focus we wanted to emphasize departmentally at Baylor,” Binetti says.

Binetti, who keeps an eye on the relatively small field of anthropology within academia, knew of Muehlenbein’s move to the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) when she made the call in 2015. The two overlapped by a few years as graduate students at Yale University.

As early as 2014, Baylor anthropology faculty began discussing a new direction — or guiding emphasis for the department — and the possible creation of a doctoral program. In the years that followed, a number of factors continued to motivate these discussions, including trends in anthropology, public health and medicine, as well as the potential for increased interdisciplinary research activity. Lee Nordt, PhD, dean of Baylor’s College of Arts and Sciences, advised the department to seek the counsel of a few outsiders in the know.

Before accepting the position, Muehlenbein recognized Baylor’s historical strengths in archaeology, forensic anthropology and applied anthropology, as reflected in the expertise of department faculty and also in the extraordinary field opportunities available to undergraduates. He wanted to capitalize on these intra-departmental strengths without replicating them. Similarly, he wanted to draw on the expertise and course offerings within other departments in building the anthropology graduate program and multiple new undergraduate minors.

EMPHASIZING HEALTH

Central to his vision, Muehlenbein saw something special in the success and popularity of Baylor’s undergraduate pre-health studies programming and the prevalence of the Baylor name within healthcare throughout the state and beyond.

“I saw opportunities to refocus the anthropology department more toward health in general,” he says. “I don’t want to call what we’re doing ‘medical anthropology’ or ‘biomedical anthropology’ because those labels actually mean something very specific to anthropologists. Within the context of a graduate program, I mean to emphasize more of a holistic understanding of health, using tools — both qualitative and quantitative — within anthropology.”

While the breadth of Muehlenbein’s training and research interests resist the sort of tidy description one might feature at the top of a professional résumé, his career to date exemplifies the interdisciplinary nature of anthropology and its critical place in the future of health-related research. His ongoing work explores evolutionary endocrinology and ecological immunology (or how and why immunity has transformed and diversified over time). He also has projects focused on global health, including emerging infectious diseases, conservation medicine and disease transmission between humans and other animals.

In 2018, the department recruited biocultural anthropologist Mark Flinn from the University of Missouri, where he served as chair of the anthropology department for nine years. Flinn’s research, broadly speaking, aims to understand how and why social relationships influence child health. Adding such faculty with research within that nexus of anthropology and human health, Muehlenbein says, will position faculty and future graduate students to receive top federal and private grant funding, an important metric as the University continues to seek R1 classification.

“As we plan for the future and think about where we want to place our PhD graduates, we want to develop a program that will equip them with skills that are marketable outside of the Academy,” Muehlenbein says.

Muehlenbein notes anthropology professors have historically trained doctoral students to become faculty members. But that model is broken, given a saturated academic job market.

“We don’t want solely to train future professors,” he says. “When we launch a PhD in anthropology with specialization in the anthropology of health, we want to make sure our graduates have a diversity of experiences and skills that could qualify them for jobs in any number of sectors. This means project-based courses that focus on applied methods as well as other unique aspects of our program.”

CAUSE FOR CELEBRATION

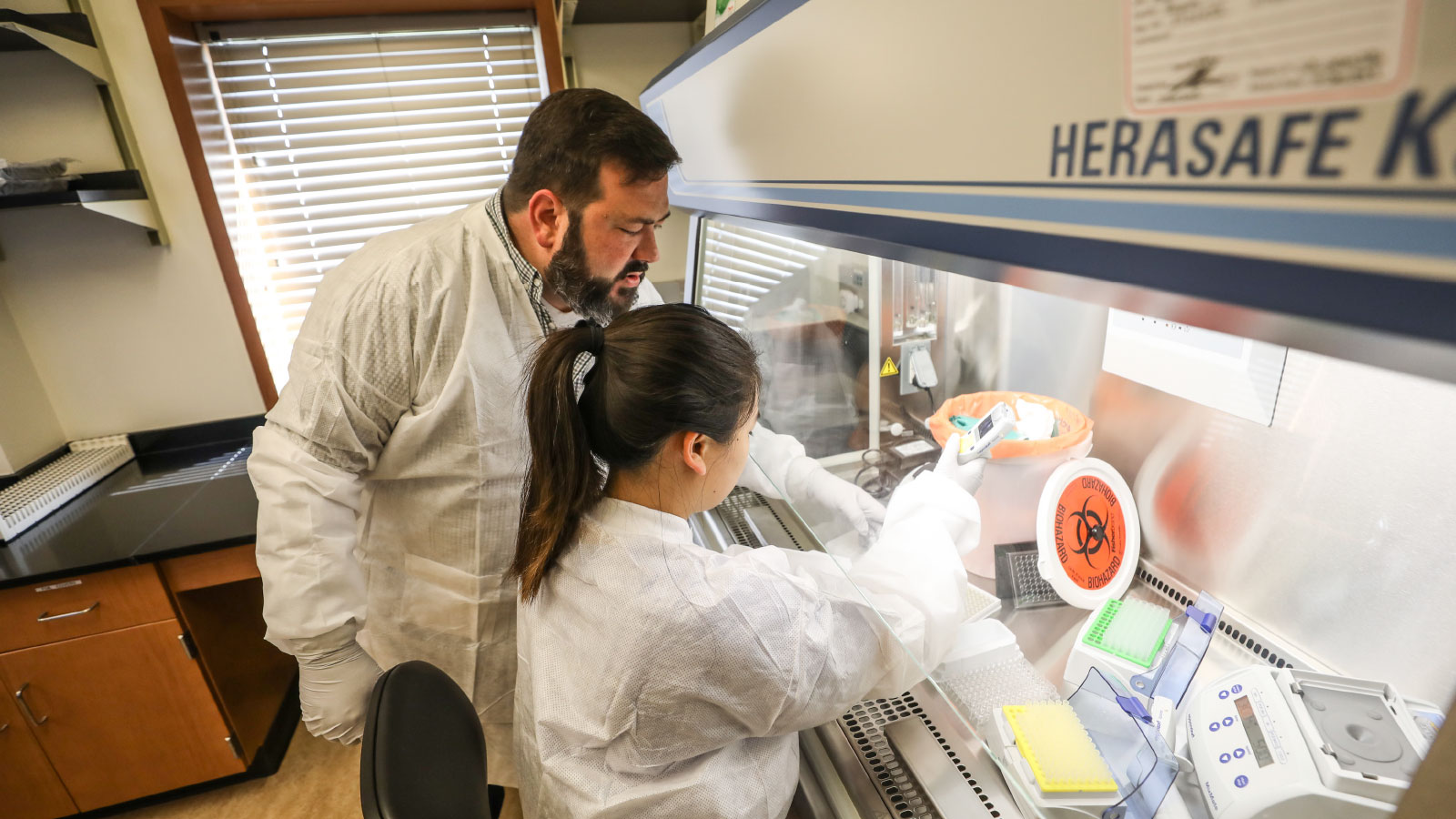

In early May, faculty from anthropology and other departments, staff from the Mayborn Museum Complex and Baylor President Linda A. Livingstone, Ph.D., gathered to unveil the new lab facilities and artifact displays. In a brief address, Muehlenbein thanked numerous supporters and voiced his eagerness to see the proposed graduate program and undergraduate minors to their official launches, better aligning the department in support of Illuminate, the University’s strategic plan, and its wide-reaching health initiative.

“From my perspective,” Baker says, “the sooner we’re able to bring in doctoral students and put them in this beautiful anthropology lab that Baylor has invested in, and have our faculty collaborating with new doctoral students, the closer we will be as a University toward our R1 goal.”