Composing a More Complete History

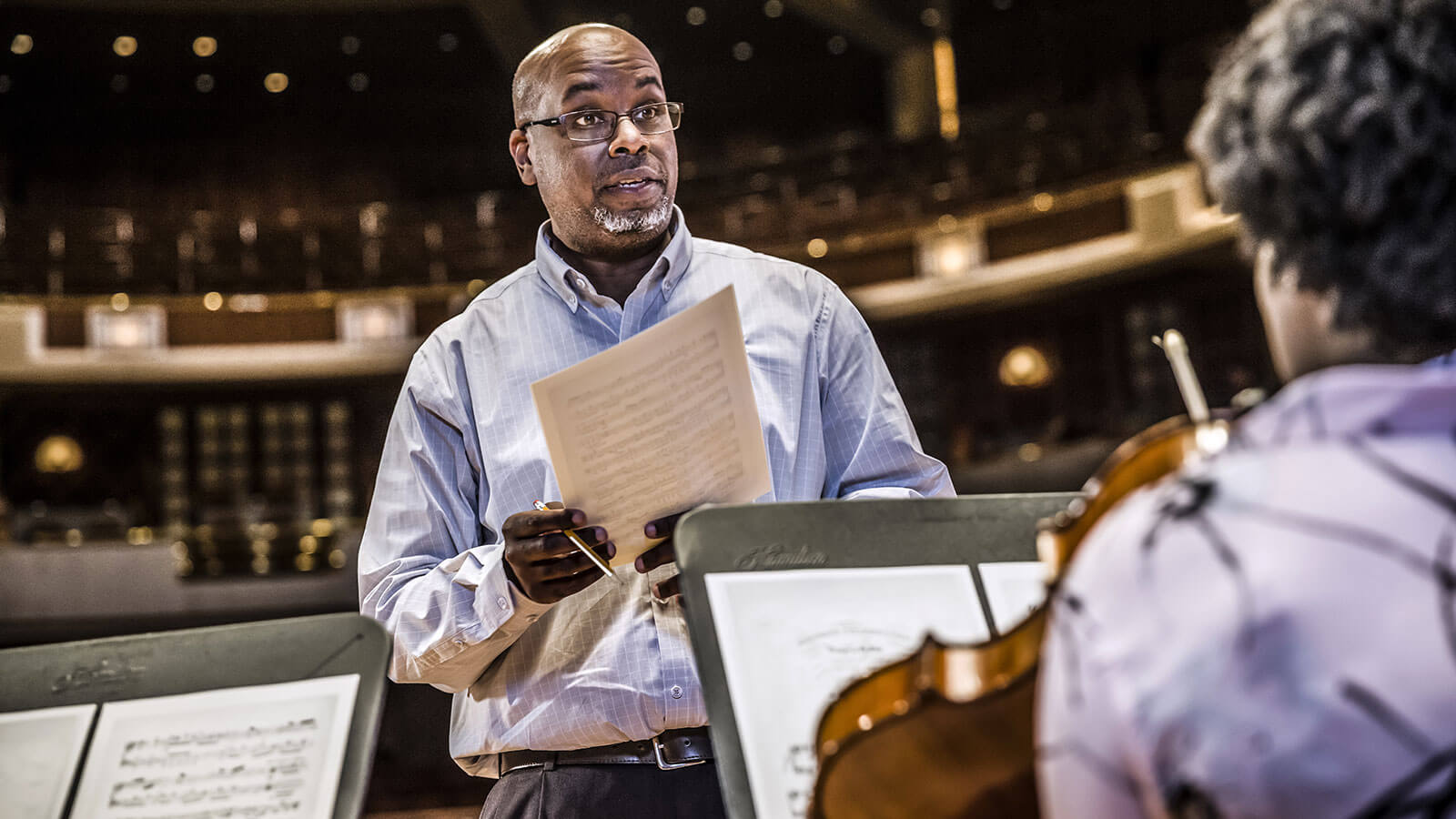

As he sifts through archives of sheet music, classical music collections and even long-shuttered piano benches, Horace Maxile, Ph.D., is doing more than searching for forgotten compositions. A national research leader on the music of Black composers, his work paints a more complete picture of music history.

Maxile, associate professor of music theory, shines a light on Black composers of classical and concert music and reintroduces their sounds to modern ears and stages.

“There is a more complete telling of the history of Western classical music to be told,” Maxile says, “and a more complete telling of the contributions of Black musicians to the world. I work to expand perspectives on the contributions of Black musicians to world culture, and to push their music beyond scholarship into performance, because the music these composers wrote was not made for me to study them, but to be performed and enjoyed.”

Filling the Void

The legendary impact of Black musicians in a variety of genres has enjoyed a great deal of scholarly attention over the last 50 years. That has not been the case, however, for the music and musicians Maxile studies.

“That’s the void that I'm trying to fill. There is a lot of material out there on jazz. The field of gospel music research is growing. Blues and spirituals have been dealt with to some degree in the literature,” Maxile says. “But, for concert music or music in the classical or Western tradition, there is definitely a void there. There are some people doing some pretty good work, but when compared to the work on jazz and other vernacular forms, there's a big void in between those two.”

His interest in the topic began in college, when Maxile first learned about Black composers like Ulysses Kay, Florence Price and William Grant Still. Intrigued by what he heard, he studied further the impact of other Black composers whose contributions had long gone unheralded. His research interest led to a career, not only in university settings but at the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago. Before coming to Baylor, he served as the Center’s associate director of research, advancing scholarly inquiry on the subject through papers, lectures and podcasts. All the while, he scoured the country, investigating physical spaces ranging from archives to composers’ homes in search of individuals and pieces deserving of a broader audience.

Maxile’s piece-specific research begins with an analysis of the music he discovers—a deep dive into the notes, emblems, and other formal attributes that comprise the piece. The context of the work is also important. Biographical information about the composer, the cultural moment in which it was produced and the audience for which it was written, a particular person or political cause which might have impacted its composition—all provide a deeper insight into the artist’s expression. Maxile synthesizes this information into articles and writings which are frequently cited in journals, dissertations, books and more.

“The thing that I’ve learned the most is to not try to put a composer in a vacuum and believe that he or she should sound a certain way in order to be considered a Black composer,” Maxile says. “There’s a wide array of ways that composers chose to express themselves and not be part of a perceived monolithic expressive voice.”

Much of his current research focuses on Jules Bledsoe, a Waco native well-known to audiences in the first half of the 20th Century as a performer. Lesser known are Bledsoe’s compositions.

“There’s definitely a discovery element to Bledsoe, and others as well,” Maxile says. “Much of his music is mostly unheard. I’m getting a sense of his compositional voice and compositional style, and comparing his approach to other composers of his day. COVID-19 forced a postponement of a concert of his music that we had put together in the Spring, but we’ll work on that when we’re able to come together again to share his music.”

Made to be Heard

In his classes, Maxile uses examples discovered in his research that provide some of the real-life examples of the theory he teaches. He came to Baylor in 2012, spurred by a desire to return to teaching. He also wanted to teach at a Christian research university where, he says, “when you talk about the ‘Hallelujah’ chorus, you can get into the ‘hallelujah’ as well as the chorus.’”

“Teaching and research definitely inform one another,” Maxile says. “I can play an example at the beginning of class to pique the interest of my students. That opens the field for discussion. From there, a student might say, ‘Can you tell me a little more about that composer? Where might I be able to find that composer’s works?’”

The students who are impacted by his lectures and the musicians who discover his research might someday be the performers who play that music for new audiences. That goal drives Maxile in his work—to give the music of Black composers a home on the modern stage and introduce them to a new generation of listeners.

“Scholarship is a vehicle to let people know about the music these composers wrote—and their music was made to be heard. If I can get people to at least consider the works, give them a shot and put them on the same program with Beethoven, Mozart or Brahms and let the works stand on their own, then I think my work is done.”